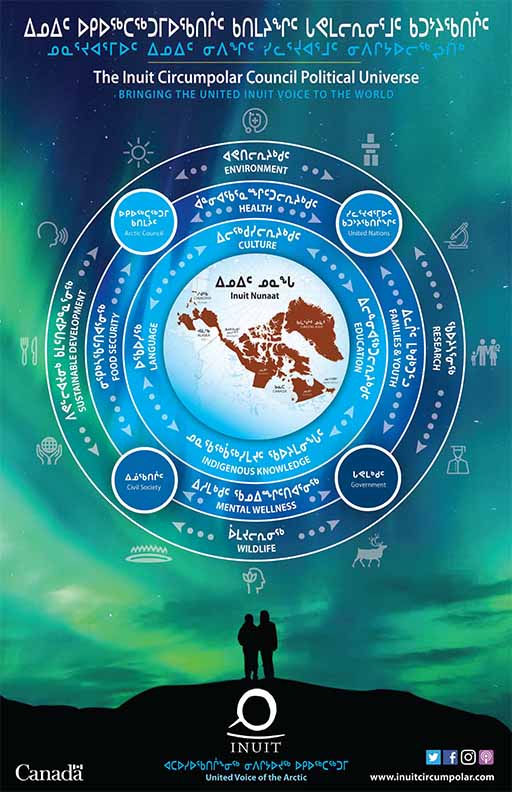

We created this poster to illustrate the political universe we bring the Inuit issues to. In the centre of our universe are Inuit – in Canada, Alaska, Greenland and Chukotka. We call our homeland Inuit Nunaat. Within Canada we call our region Inuit Nunangat, which includes the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Nunavut, Nunavik, and Nunatsiavut.

Surrounding the centre, we list the issues that we bring to important global forums. The issues come from the Declarations adopted at the ICC General Assemblies, held every four years. In this poster they are: Culture, Education, Language, Indigenous Knowledge, Health, Families and Youth, Mental Wellness, Food Security, Environment, Research, Wildlife, and Sustainable Development. These issues interact with each other as indicated by the arrows.

We bring these issues to the Arctic Council, the United Nations, Government, and Civil Society forums. We are guided by Inuit, represented by elected Inuit leaders and delegates who attend our General Assemblies and Summits. As the poster says, we are “Bringing the United Inuit Voice to the World”.

Along with this poster we have developed some more specific background documents related to the forums we work in. Specific to Canada, ICC has contributed the International Chapter of the Arctic and Northern Policy Framework, released in 2019. We have created a backgrounder on the International Chapter. Also find a backgrounder on the United Nations. It lists the majority of the UN bodies we participate in. Finally, please find a backgrounder on the Arctic Council, which ICC was instrumental in creating in 1996 in Ottawa.

With this poster and accompanying backgrounders, we hope you will gain a stronger appreciation of how ICC is bringing Inuit issues to the international arena.

ICC Backgrounder: Arctic Council

The Arctic Council (AC) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental forum for Arctic cooperation. The first step towards its creation took place in 1991 when eight polar nations signed the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS). We are proud of the work we have done towards the creation of the Arctic Council, notably the efforts of former ICC Chair Mary Simon. It was founded in Ottawa on September 19, 1996, and Canada was the first Chair from 1996-1998. The Chair of the Arctic Council rotates every two years.

The Arctic Council is composed of eight Arctic States – Canada, USA, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Russia, Iceland, and Denmark. Only states with territory in the Arctic can be members.

The main meetings are AC Ministerial, held every two years. The Senior Arctic Official (SAO) meetings take place during the year to conduct the work of the AC as determined at AC Ministerial meetings.

ICC is one of the six Indigenous Permanent Participant Organizations. The category of Permanent Participants was created to provide for the active inclusion and full consultation with the Arctic indigenous representatives within the Arctic Council. This principle applies to all meetings and activities of the Arctic Council.

Permanent Participants may address the meetings, and raise points of order that require immediate decision by the Chairman. Agendas of Ministerial Meetings need to be consulted beforehand with them; they may propose supplementary agenda items. When calling the biannual meetings of Senior Arctic Officials, the Permanent Participants must have been consulted beforehand.

Permanent Participants may propose cooperative activities, such as projects. All this makes the position of Arctic indigenous peoples within the Arctic Council quite unique compared to the (often marginal) role of such peoples in other international governmental fora. However, decision making in the Arctic Council remains in the hands of the eight member states, on the basis of consensus. The Permanent Participants are supported by an Indigenous Peoples Secretariat (IPS), which is based in Tromsø, Norway.

There are over a dozen “Observer States” at the Arctic Council. Observers have no voting rights at the Arctic Council.

The Arctic Council’s work has led to the development of other forums that examine specific issues, such as coordinated response to emergencies at sea through the Arctic Coast Guard Forum; economic development through the Arctic Economic Council; and circumpolar education and research through the University of the Arctic (UArctic).

The Arctic Council has provided a forum for the negotiation of three important legally binding treaties on scientific cooperation, oil spill preparedness and response, and search and rescue. The first was the 2011 Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement. Treaties have also been negotiated outside the auspices of the Arctic Council on issues such as fisheries, polar bear and caribou management, to name only a few.

The Arctic Council regularly produces comprehensive, cutting-edge environmental, ecological and social assessments through its Working Groups (ACAP, AMAP, CAFF, EPPR, PAME, and SDWG). ICC is active in each Working Group. Greater details of our activities in these areas are chronicled in the ICC (Canada) Annual Reports, as well as the Activities Reports associated with our General Assemblies, held every four years.

The Working Groups execute the projects and projects mandated by the Arctic Council Ministers, as stated in Ministerial Declarations, the official documents that result from Ministerial Meetings.

Here is a full list of the Arctic Council Working Groups:

- Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP)

- Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP)

- Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF)

- Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response (EPPR)

- Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME)

- Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG)

Each working group has a website, with complete details of their respective activities.

ICC Backgrounder: United Nations

ICC’s vision was always to work within the United Nations, and its many associated bodies, to advance the human rights of Inuit, and other concerns such as the protection of wildlife and the environment. In 1983 ICC was granted “Consultative Status” at the UN under the Economic and Social Council – known as ECOSOC.

In 2000 the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) was created. The Arctic was recognized as a region providing Inuit and Saami with a seat on the forum. The Permanent Forum is the key UN body dealing with indigenous rights.

In addition, the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) advises the UN Human Rights Council.

It is by working within the United Nations that Inuit have contributed to creation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted on September 13, 2007. This historic document is a vital tool for Inuit in the ongoing struggle to protect our human rights, cultural traditions, economic advancement, and political development.

We have contributed to scientific studies on the ravages of climate change such as the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). We’ve worked diligently at the Conference of the Parties (COP meetings) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to bring a consistent message regarding the harmful effects climate change is having on our Arctic homeland.

ICC is active within the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). It is the leading global environmental authority that sets the global environmental agenda, promotes the coherent implementation of the environmental dimension of sustainable development within the United Nations system, and serves as an authoritative advocate for the global environment.

UNEP’s mission is to provide leadership and encourage partnership in caring for the environment by inspiring, informing, and enabling nations and peoples to improve their quality of life without compromising that of future generations. It is headquartered in Nairobi, Kenya.

Its work is categorized into seven broad thematic areas: climate change, disasters and conflicts, ecosystem management, environmental governance, chemicals and waste, resource efficiency, and environment under review.

ICC has made significant gains in one of the UNEP instruments known as the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, known as POPs. It is a global treaty to protect human health and the environment from chemicals that remain intact in the environment for long periods, become widely distributed geographically, accumulate in the fatty tissue of humans and wildlife, and have harmful impacts on human health or on the environment.

Exposure to POPs can lead to serious health effects including cancer, birth defects, dysfunctional immune and reproductive systems, greater susceptibility to disease and damage to the central and peripheral nervous systems. Given their long range transport, no one government acting alone can protect its citizens or its environment from POPs. In response to this global problem, the Stockholm Convention, adopted in 2001, requires its parties to take measures to eliminate or reduce the release of POPs into the environment.

Similarly, the Minamata Convention on Mercury, adopted in 2013, is a global treaty to protect human health and the environment from the adverse effects of mercury. It came into force in 2017. The Convention draws attention to a global and ubiquitous metal that, while naturally occurring, has broad uses in everyday objects and is released to the atmosphere, soil and water from a variety of sources. Controlling the release of mercury throughout its lifecycle has been a key factor in shaping the obligations under the Convention.

Major highlights of the Minamata Convention include a ban on new mercury mines, the phase-out of existing ones, the phase out and phase down of mercury use in a number of products and processes, control measures on emissions to air and on releases to land and water, and the regulation of the informal sector of artisanal and small-scale gold mining.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is an international treaty adopted in 1982. It replaced the four Geneva Conventions dating back to 1958 which concerned the territorial sea and the contiguous zone, the continental shelf, the high seas, fishing and conservation of living resources on the high seas. UNCLOS has created three new institutions: The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea; the International Seabed Authority; and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

ICC is involved with UNCLOS at the International Maritime Organization (IMO) regarding shipping and the use of heavy fuel oils in the Arctic, for example, as well as at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCUN) regarding the protection of wildlife in the Arctic.

UNCLOS has become the legal framework for marine and maritime activities. The IUCN with its partners are working towards an implementation agreement (UNCLOS IA) that will close important gaps in governance.

The IUCN is a membership Union composed of both government and civil society organizations. It works with the United Nations. It harnesses the experience, resources and reach of its more than 1,400 member organizations and the input of more than 17,000 experts. ICC is a member of the IUCN. This diversity and vast expertise makes IUCN the global authority on the status of the natural world, and the measures needed to safeguard it.

One of the important instruments from the IUCN is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international agreement between governments. Its aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species.

ICC is actives at CITES meetings to protect Inuit trade in polar bear, as well as narwhal and walrus ivory, for example. Annually, international wildlife trade is estimated to be worth billions of dollars and to include hundreds of millions of plant and animal specimens. The trade is diverse, ranging from live animals and plants to a vast array of wildlife products derived from them. Levels of exploitation of some animal and plant species are high and the trade in them, together with other factors, such as habitat loss, is capable of heavily depleting their populations and even bringing some species close to extinction. Many wildlife species in trade are not endangered, but the existence of an agreement to ensure the sustainability of the trade is important in order to safeguard these resources for the future.

Because the trade in wild animals and plants crosses borders between countries, the effort to regulate it requires international cooperation to safeguard certain species from over-exploitation. CITES was conceived in the spirit of such cooperation. Today, it accords varying degrees of protection to more than 37,000 species of animals and plants, whether they are traded as live specimens, fur coats or dried herbs.

A significant initiative with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has been the adoption of a set of goals – known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). They aim to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all as part of a new 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

This is very much in the spirit of the ICC founding vision. Adopted by all UN Member States in 2015, the 2030 Agenda provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet. At its heart are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are an urgent call for action by all countries – developed and developing – in a global partnership. They recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests. The SDGs build on decades of work by countries and the UN, including the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Here is a short list of the United Nations forums, and conventions ICC is active in:

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII)

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

- United Nations International Maritime Organization (IMO)

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

- Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)

- Minamata Convention on Mercury (Minamata Convention)

- United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals (DSDG)

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

Each of these organizations has a website of its own, with comprehensive information about its activities.

ICC Backgrounder: Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework – International Chapter

In October, 2019 the Canadian government published its new Arctic and Northern Policy Framework, which was several years in the making. Within Canada, Indigenous groups contributed to the development of the policy. In the case of the International Chapter, the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) was involved with consultations and contributing to the final draft.

The International Chapter is part of a larger policy document called “Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework” which contains eight major goals and corresponding objectives. The six goals contained in the International Chapter reflect and complement the goals in the main document.

The International Chapter begins with defining the contemporary reality in the circumpolar region. The Arctic Council plays a vital role in the policy in that Canada is one of the eight states that compose the Arctic Council. ICC is one of the six indigenous peoples’ organization Permanent Participants.

Established in 1996 in Ottawa, with substantial foundational work contributed by former ICC Canada Chair Mary Simon, the Arctic Council brings together Arctic states, Indigenous peoples and observers to address sustainable development and environmental protection of the Arctic.

The International Chapter notes the growing interest in the Arctic. Thirteen non-Arctic states from Europe and Asia have been admitted as accredited observers to the Arctic Council. Many have developed their own Arctic policies and strategies, seeking to increase engagement in the region.

Global interest is surging in the circumpolar area. Climate-driven changes are making Arctic waters more accessible, leading to growing international attention to the prospects for Arctic shipping, fisheries and natural resources development. At the same time there are increased international efforts in protecting the fragile Arctic ecosystem from the impacts of climate change.

The document states that “Canada will continue to exercise the full extent of its rights and sovereignty over its land territory and its Arctic waters, including the Northwest Passage.”

The chapter lists three key opportunities:

- Strengthen the rules-based international order in the Arctic.

- More clearly define Canada’s Arctic boundaries, including defining the outer limits of Canada’s continental shelf in the Arctic ocean.

- Broaden Canada’s International engagement to contribute to the priorities of Canada’s Arctic and North. This includes socio-economic development, enhanced knowledge, environmental protection and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

To meet these three key opportunities, Canada’s international activities will be guided by the following six goals:

- The rules-based international order in the Arctic responds effectively to new challenges and opportunities.

- This is a substantial section containing four key objectives:

- Bolster Canadian leadership in multilateral forums where polar issues are discussed and decided upon.

- Enhance the representation and participation of Arctic and Northern Canadians in relevant international forums and negotiations.

- Strengthening bilateral cooperation with Arctic and key non-Arctic states and actors.

- Defining more clearly Canada’s marine areas and boundaries in the Arctic.

- Canadian Arctic and Northern Indigenous peoples are resilient and healthy.

- With this goal Canada intends to contribute to the following objectives:

- Eradicate hunger.

- Reduce suicides.

- Strengthen mental and physical well-being.

- Create an environment in which children will thrive, through a focus on education, culture, health and well-being.

- Close gaps in education outcomes.

- Provide ongoing learning and skills development opportunities across international boundaries.

- Strong, sustainable, diversified and inclusive local and regional economies.

- With this goal the objective is to enhance opportunities for trade and investment.

- Knowledge and understanding guides decision making.

- This goal supports increasing international polar science and research collaboration with the full inclusion of Indigenous knowledge.

- Canadian Arctic and Northern ecosystems are healthy and resilient.

- Many objectives support this goal, including:

- Accelerate and intensify national and international reductions of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and short-lived climate pollutants.

- Ensure conservation, restoration and sustainable use of ecosystems and species.

- Support sustainable use of species by Indigenous peoples.

- Partner with territories, provinces and Indigenous peoples to recognize, manage and conserve culturally and environmentally significant areas.

- Facilitate greater understanding of climate change impacts and adaptation options through monitoring and research, including Indigenous-led and community-based approaches.

- Enhance support for climate adaptation and resilience efforts.

- Enhance understanding of the vulnerabilities of ecosystems and biodiversity and the effects of environmental change.

- Ensure safe and environmentally-responsible shipping.

- Strengthen pollution prevention and mitigation regionally, nationally, and internationally.

- Reconciliation supports self-determination and nurtures mutually respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

- The main objective in support of this goal is to reclaim, revitalize, maintain and strengthen the cultures of Arctic and Northern Indigenous peoples, including their languages and knowledge systems.

The International chapter is online here:

(English) https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1562867415721/1562867459588

(Inuktitut Syllabics) https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/iku/1562867415721/1562867459588

Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework is online here:

(English) https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1560523306861/1560523330587#s6